You’ll be happier, and achieve more, if you’re kinder to yourself

Great Work core idea no. 3

I hope this time of year’s a good one for you. Happy anything you may celebrate. I have a few things for you this time.

Be kinder to yourself and achieve more

Done right, most of us, most of the time, can achieve more, and enjoy it more, by being kinder to ourselves.

I took too long, last week, to realize that I was pushing myself too hard and needed to be kinder to myself. And then one of Oliver Burkeman’s emails appeared in my inbox (he’s the Four Thousand Weeks guy and his emails are great—details here). This one said, among other things:

… So it’s worth at least seeing what happens when you ask yourself not what you ought to be doing with your time, but what you’d like to be doing. And allowing for the possibility that the results of that approach might include all the productivity and accomplishment you’d previously been trying to attain by yelling at yourself.

And that was just what I needed to hear. And well-timed: in this short series of emails I’m reviewing the seven core principles that underpin Great Work ideas, and here’s the third:

Done right, most of us, most of the time, can achieve more, and enjoy it more, by being kinder to ourselves.

This risks sounding trite—a nice idea that can’t realistically change your real working life. But it turns out that there are changes that almost all of us can make, now, that will immediately improve our lives and work.

(Nine percent of you may hear an echo here, as I wrote about this right when I began this Great Work newsletter. But that was before 91% of you had signed up, and this is one of the most life-changing Great Work ideas.)

Most of us are pushing ourselves too hard

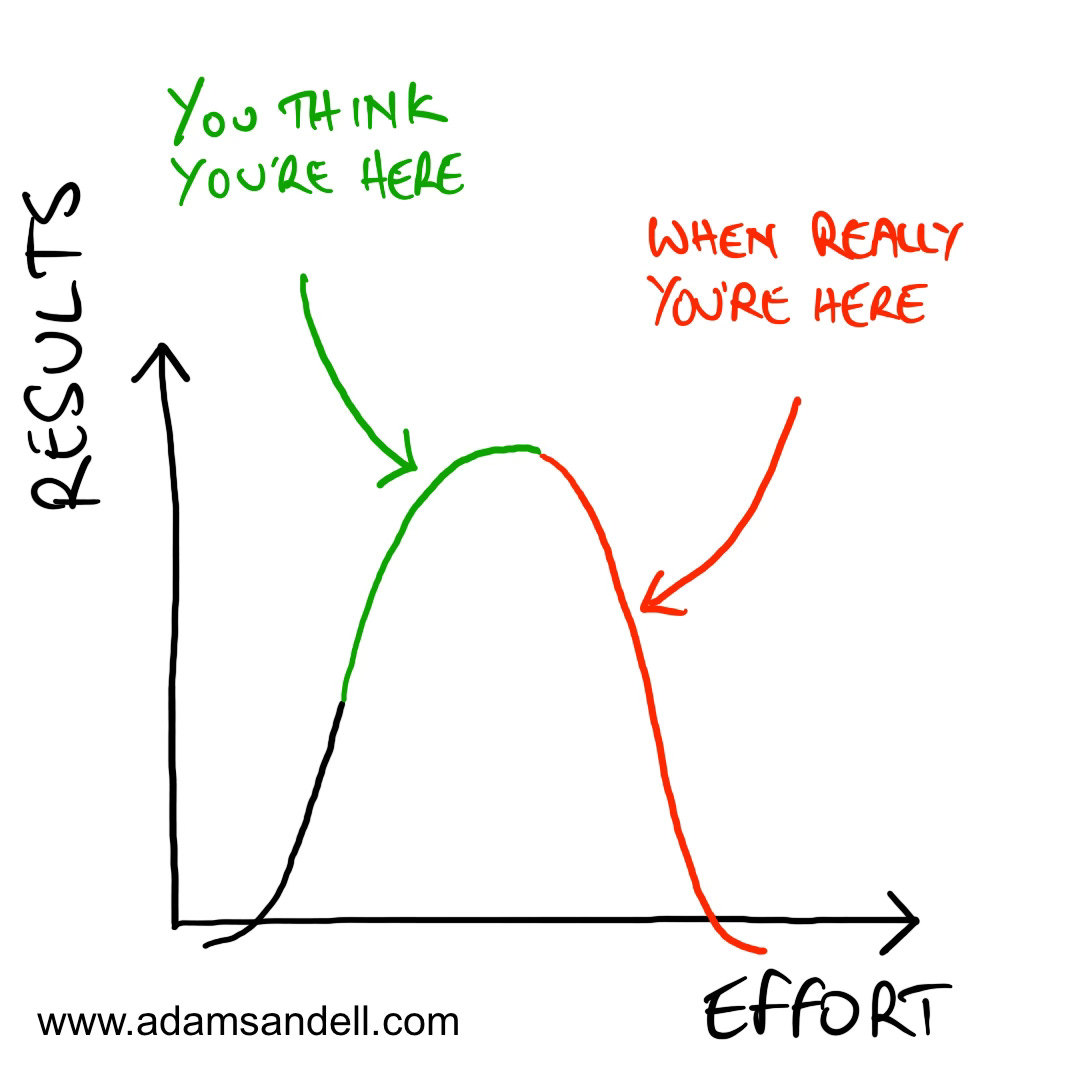

Have a look at this beautifully- (or at least unintentionally festively-) drawn sketch:

This says: work harder, and you’ll achieve more—up to a point. Lots of research, from many perspectives, over decades, indicates that most of the time, most of us are on the right side of that curve. On the right side, the only way to do better is to be kinder to yourself—to move yourself to the left of where you are. On the right side, if you work even harder, you’ll do even worse.

Let’s be clear: this is not about being a lightweight. If you’re serious about achieving more it’s what you have to do. That it feels great is merely a bonus.

We know from multiple sources that most of us are on the right side of that curve. One source is four-day week studies, which have involved thousands of people in all sorts of organizations, commercial and non-profit, all around the world.1 The working week switches from five days to four, with no reduction in pay. Consistently, business revenues increase, recruitment improves, staff turnover reduces, and workers love it. This is a huge finding: people are paid the same for four days as they were for five, days off increase by 50%, teams achieve more, everyone’s happier, and the large majority of employers like it so much that, at the end of the trial, they continue it. (It’s also better for the climate.2)

Much evidence points the same way. Back in the 1950s, Raymond van Zelst and Willard Kerr, two academics at Illinois Tech, surveyed their colleagues and discovered that those who spent more hours in the office were less productive: fewer publications and inventions than those who worked less hard.3 The same went for those who put in time at home: their productivity increased up to a point, but more hours reduced their productivity. A much more recent experiment by Boston Consulting Group, one of the “big three” US management consulting firms (a notoriously “always on” industry), involved protecting people from intrusions, or even checking email, after 6 p.m. one night a week. They saw measurable improvements in the quality of people’s work, communication, and team efficiency and effectiveness.

If you’re interested, the mechanism for this, the reason why rest is so essential to our performance, is partly because it switches on a part of our brain called the default mode network, which plays an important role in our intelligence, the performance of complex tasks, memory, social and emotional functioning, mental health, and more. (More on that in the two books I recommend below.)

There’s now so much evidence from all sorts of industries that we mostly hang out on the right side of that effort/results curve, and the conclusion is inescapable: you are likely achieving less than you would if you went easier on yourself, and the only way to do better is to slow down.

So the question isn’t whether looking after ourselves better works: it’s why we don’t.

Some people aren’t aware of, or don’t buy, the effort/result curve. (And that sometimes looks a lot like an excuse for not tackling long-established patterns of behavior.)

But more often we know we’re on the right (i.e. wrong) side of the effort/results curve, but we tell ourselves—and I’ve heard this from people in all walks of work—that it’s all very well for other people, but in my job it just isn’t possible to slow down.

Let’s see if that’s true.

Can you slow down, in your real job? How?

As a GP who sometimes works in emergency rooms, I have some experience of work where it’s easy to think it just isn’t possible to slow down. (Google tells me my most searched-for article here ever was about how I used rest and other forms of kindness to myself to get through a really tough week at work.) The other job where I most commonly hear people say, “But in this job, there isn’t anything I can do to go easier on myself,” is teachers, with classes that need to be taught, lessons prepared, kids’ work marked, and kids and parents listened to.

Here are some things that we can all do, including me as a doctor with patients to see, to shift ourselves left on that effort/results curve:

Start by paying attention to where you are on your effort/results curve. If, like most of us, you naturally gravitate toward the right side of the curve, nothing’s going to change if you’re not aware of where you are. You can’t manage your time or your tasks unless you first manage your energy, and focusing on managing your energy may be all you need to do to get on top of everything else.

Give breaks the highest priority you can. Protect them at all costs: they are vital to maintain your function and performance. In jobs like mine, and maybe yours, this may call for occasional tolerance with keeping people waiting, and that has to be OK: no one wants to be looked after by a doctor who’s dopey from exhaustion, nor taught by a teacher whose heart isn’t in it.

Break first. If you know you need five minutes to yourself and you also have something pressing to get done, take that five-minute break first. After that, a little refreshed, you’ll do whatever needs doing with a clearer head, more efficiently, and better.

Break well. Scrolling Instagram isn’t a break—it’s a maladaptive waste of precious rest time. Going for a walk outdoors or closing your eyes for a few minutes are true rest. You’ll know what does it for you: as a rule of thumb, if it facilitates daydreaming or meandering thoughts, it’s rest. If it doesn’t, it probably isn’t.

Stop working when the day should end. If it’s late and you’re tired, stop. (The rule I used to follow, get today’s work done today, has some merit as an approach to keeping on top of things, but only if it gives way to the overriding need to take care of yourself.)

Build as much rest into your week as you can. If you know you’re going to have several heavy days, ensure there’s time for you at some point, even if only in the evenings, and time to unwind (rather than turn straight to your email inbox or the tax return) as soon as you can.

Plan leisure. Your time off can easily fill with chores and the administration of life. Each week should have time not just for rest but, within that, for leisure, whatever that means for you—reading, seeing people you care about, getting outdoors, watching a drama on the TV, or something else. (Again, it ain’t scrolling.)

Let nothing encroach on getting a good night’s sleep. Every night.

How does that sound?

And if this is a holiday season for you, a time when you reflect on how you’d like to shape your next year, how much of that could you start practicing, turning it into a habit?

Want to read more on this?

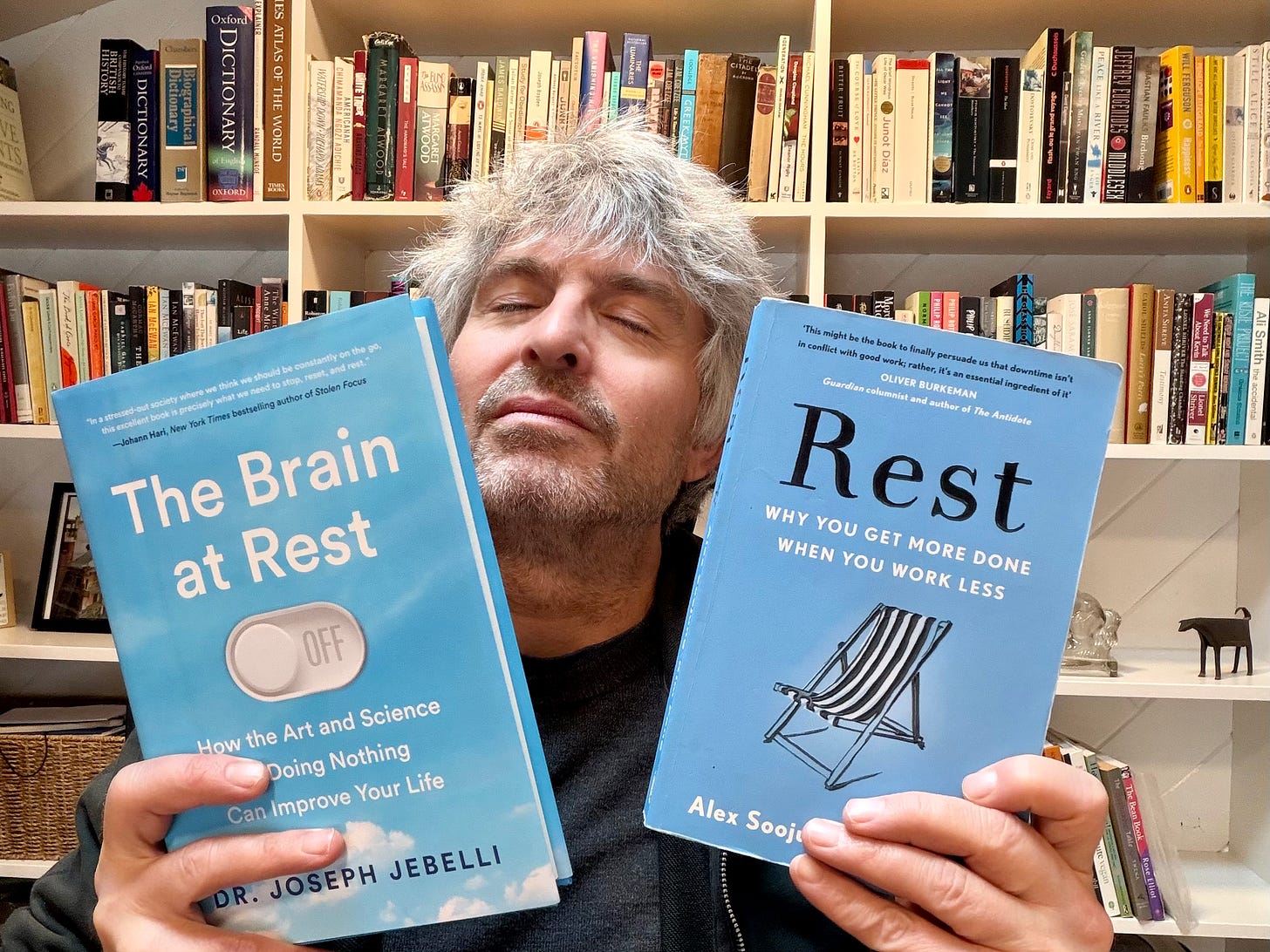

I regularly recommend Alex Soojung-Kim Pang’s book Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less (Basic Books, 2016) because it’s been so influential on my thinking about this, my life, and, obviously, this piece. It’s a wonderful book.

A new book on rest was published this year, neuroscientist Joseph Jebelli’s The Brain at Rest: How the Art and Science of Doing Nothing Can Improve Your Life (Random House, 2025). I wondered whether we needed another book on rest but it turns out we do: a fascinating, readable account of what rest does for us and how it can change your life.

How could this be better?

I want to make these emails and podcasts more useful to you. Would you do me a one-minute favor? Click here and answer two questions—what you like about Great Work, and how it could be better. Thank you!

Winter at Great Work Towers

I’m writing this on the shortest day of the northern hemisphere’s year. This winter I’ve been trying to follow the advice of Kari Leibowitz in her book How to Winter. I normally dread the winter but, as she explains, that’s the problem. I reviewed her book here and, so far, my winter’s been transformed by the approach she suggests—none of the grumpiness that normally colors this time of year for me. But damn, I’m pleased that the days are starting to lengthen again.

After a year or two of overworking as a doctor, I’m having a writing sabbatical, mainly working on the Great Work book (and just a little teaching and coaching). I’m loving it. I’m currently about half-way through turning the second draft into a third, trying to turn it into something I’d be willing to show to editors and agents. It’s interesting, as I live this idea that you get more done and do it better by being kinder to yourself, to feel my creativity and enthusiasm return.

Perimenopausal Great Work

Next month I’m doing a webinar for PAMELA, a UK-based support network for female legal-aid lawyers, focused on menopause and perimenopause. We’ll be talking about sleep and managing exhaustion while doing tough work. It’s at 1 pm UK time on Friday 16 January—a short talk and then discussion. You don’t have to be a legal-aid lawyer (my old job) or in the UK to join: being a woman with an interest in the (peri)menopause is fine! If you’re interested, sign up here, and I’d really appreciate it if you’d let me know you’re coming!

At the moment my next Great Work speaking thing is at the BC Rural Health Conference in Prince George, BC, in May. Want me to speak at your thing?

The year ahead

For the last few years I’ve worked as a doctor at a clinic and hospital on a remote Indigenous reserve (reservation, in US English) on an island in the Canadian Pacific Ocean. I’ll be picking up my stethoscope again in February, also on a reserve on a beautiful Pacific island, but this time just a few miles from home. I’m so grateful for the opportunity to do the work I do.

This time last year, this Great Work newsletter had about 500 readers. We now have about 1,800, plus listeners to a professionally edited podcast version (thanks, Bren!). That’s still a long way short of the “platform” I need for a heavyweight publisher to be interested in the book. And that makes it hard for introverted folk who don’t like social media to get published! If you find anything useful here and there’s anything you can do to spread the word, I’d be hugely grateful.

Thanks so much for being part of this, for taking the time to read the stuff I write. I don’t take it lightly that you allow me into your inbox. I wish you serenity and success in your meaningful work in 2026. Meanwhile,

New here? Not yet joined this community of people who do tough work that matters? Sign up! It’s free, practical, evidence-based, never spam, and bullshit-free. ⤵

And, if you find Great Work useful, please do share it with others who might like it too. Thank you! ⤵

Are you a LinkedIn person? ⤵

See 4 Day Week Global’s research, and also here, here, here, and Johann Hari, Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again (New York: Crown, 2022), 187–190.

Raymond H. Van Zelst and Willard A. Kerr, “Some Correlates of Technical and Scientific Productivity,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 46 (1951): 470–75, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063045; Raymond H. Van Zelst and Willard A. Kerr, “A Further Note on Some Correlates of Scientific and Technical Productivity,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 47 (1952): 129–129, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0058912; see also Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less(London: Penguin Life, 2017), 62–64.