Overwhelmed by All You Need to Get Done?

Time-boxing actually helps

The podcast version is now being professionally edited. Have a listen above, or on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or YouTube.

This time: time-boxing, and a book review.

“Important-seeming things often sit on my ‘To Do Today’ list for weeks until I eventually abandon them.”

Daunted by your list of things to do? The most important change of perspective may be the realization that most of these things are never going to get done—and that’s fine. The definitive book about all this is Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman. If you struggle with how much you have to do and you haven’t read Four Thousand Weeks, you really should.

But we still need to get some stuff done. And, if you want an approach to that, a structure for getting way more done while looking after yourself and being realistic about how much you truly can get done, the only techniques that truly work all seem to be based on some sort of time-boxing or time-blocking. I recently returned to time-boxing, after a lapse of a few years, and I’m wondering why I lost the faith. It’s not for everyone. But it makes me and many others way more productive—and more relaxed and rested. And you don’t have to go all-in: you’ll benefit from doing just a bit.

What is time-boxing?

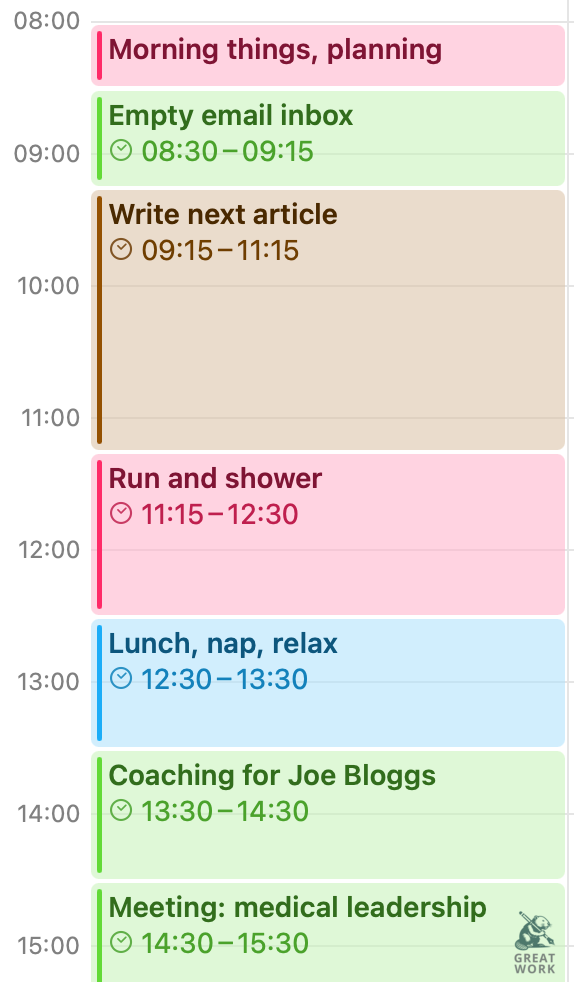

The idea’s simple. Each day, when your head’s clear, perhaps first thing in the morning, you decide what your priorities are for that day: maybe a project (work or life), tasks, rest, time with people who matter to you, exercise, the administration of life, and the other important stuff.

This is, obviously, for those parts of the day, and those days, over which you have some flexibility. If you’re a teacher with seven scheduled hours or a nurse working a twelve-hour shift, you could time-box outside of those hours, and your unscheduled days.

Then you block out realistic amounts of time throughout the day for those priorities you identified. You feed things from your to-do list into a calendar in relatively small chunks of time. At 9 am, half an hour for this, followed by an hour and a half for that. Then an hour of this.

If your priority today is to spend the first six hours mooching around in your dressing-gown, time-box that, so it doesn’t get intruded upon by the bothersome work email you’re tempted to re-read, or (unless this is what you subsequently decide) by a spur-of-the-moment plan to tackle a DIY job.

And then you follow those blocks of time, focusing only on what you’d planned to do, modifying the plan as needed if something takes longer than expected or your schedule gets derailed.

And that’s more or less it.

Why?

Three huge benefits:

It forces you to be realistic about what you can get done in a day. My time-management Achilles’ heel is being wildly unrealistic about how much I can get done—and then feeling disappointed with myself at the end of the day when I haven’t achieved the impossible. With time-boxing you quickly learn that (for example) it’ll take about eight hours to write this article, record the podcast, and get it all ready to go out—not the two hours I began by allocating to it.

It allows you to prioritize the things that matter most, controlling those things that otherwise colonize a large chunk of your day (remember Parkinson’s law, that tasks expand to fill the time you make available to them). Time-boxing helps you ensure you actually get to the exercise you intended, or the rest that’s necessary to be more productive, or the time that you wanted to spend with your partner or kids.

It focuses you fully on one thing at a time, knowing you’ve made time elsewhere in the day for the other stuff on your mind.

In Four Thousand Weeks, Oliver Burkeman writes that “The real measure of any time management technique is whether or not it helps you neglect the right things.”1 That’s the strength of time-boxing, leaving you more focused on what matters most.

If it’s not for your typical work days, because you’re the teacher with the full day of classes, the manager with a day of meetings, or me in a clinic or emergency room, it may be particularly valuable for days off that otherwise get consumed by chores at the expense of true leisure, for holidays where you find it hard to unwind because of the shapelessness of the day, and (I suspect), for retirement or sabbaticals, when those familiar with the structure of work often struggle.

It sounds horrible!

For some, including me, the thought of having things planned to this level is constraining, perhaps even stressful. I often want to be able to roll with how I’m feeling, be spontaneous, not micromanage myself or fit my days into tiny boxes on a calendar.

But we do have to do some thinking about how to balance what we want to get done today, and this week, if we want it remotely to reflect our wishes—including for rest and leisure, which tend to be marginalized. You can always alter your plan during the day. And the returns from time-boxing are immense. It’s not magic, but it may be the best way of ensuring that you do in fact have the day, and cumulatively live the life, that you want. To the extent that it’s a bit finicky, that may be a price worth paying.

And of course you can do it as much or as little as you want—just your mornings, your exercise, your social media use, or the spare-time writing of your novel.

It probably can add to your stress if you approach it as another thing you have to do, rather than as a helpful tool. The trick, I think, is to recognize that, if it starts going awry, you need to modify your approach. If, like me, you tend to wildly underestimate how long things will take, learn and recalibrate. (By making me more realistic, it’s reduced my stress about getting things done.) If it makes you feel you’re rushing from one thing to another, loosen it up, and build in more time to relax.

The effects

It makes you reflect on, and then prioritize, whatever’s most important to you.

It helps you ensure you build enough rest into each day. Remember the core Great Work idea that you’ll get more done, and do it better, if you take rest more seriously.

It greatly reduces rapid switching between tasks, which is much more cognitively draining than we realize.2 It’s much easier to ignore notifications and interruptions if you know that you’re focusing on something for 45 minutes and can check after that.

It makes it easy to schedule, and therefore contain, your internet time. If you’re someone who can’t resist checking your email inbox every ten minutes, or who inexplicably hasn’t disabled notifications for new email and looks at email the moment it arrives, you could probably schedule fifteen minutes every hour for email and still be more productive and less drained by the end of the day.

It works nicely alongside the pomodoro technique. (This is a simple and startlingly effective strategy for work where you need to focus. At its simplest you use a timer to work in 25-minute blocks. After each 25 minutes of work, you have a five-minute break—or, every so often, longer. Each break clears your head and you work, and feel, way better.)

It helps you use your leisure time the way you want to be using it—instead of filling it with chores or distractions and never doing the meaningful, nourishing things you really want to be doing with your time off.

I wonder whether, for those who, like me, are prone to grazing, it helps with healthier eating habits, too: you know what you’re doing next, so there’s less reason to distract yourself by looking to see if there’s anything appealing in the fridge.

It’s not perfect. It bothers me when the plan starts going awry—as of course plans do. (The book I’m about to recommend has good strategies for dealing with this.) And I sometimes feel a rebellious resistance to begin a time-boxed task that, in a less planned day, I might have turned to willingly. Perhaps I’m still not planning enough leisure.

But the measure isn’t does it solve all my problems perfectly? The measure (and here I depart a little from Oliver Burkeman) is does it significantly improve my life? And the answer to that, for me, is: Oh wow, yes!

The book

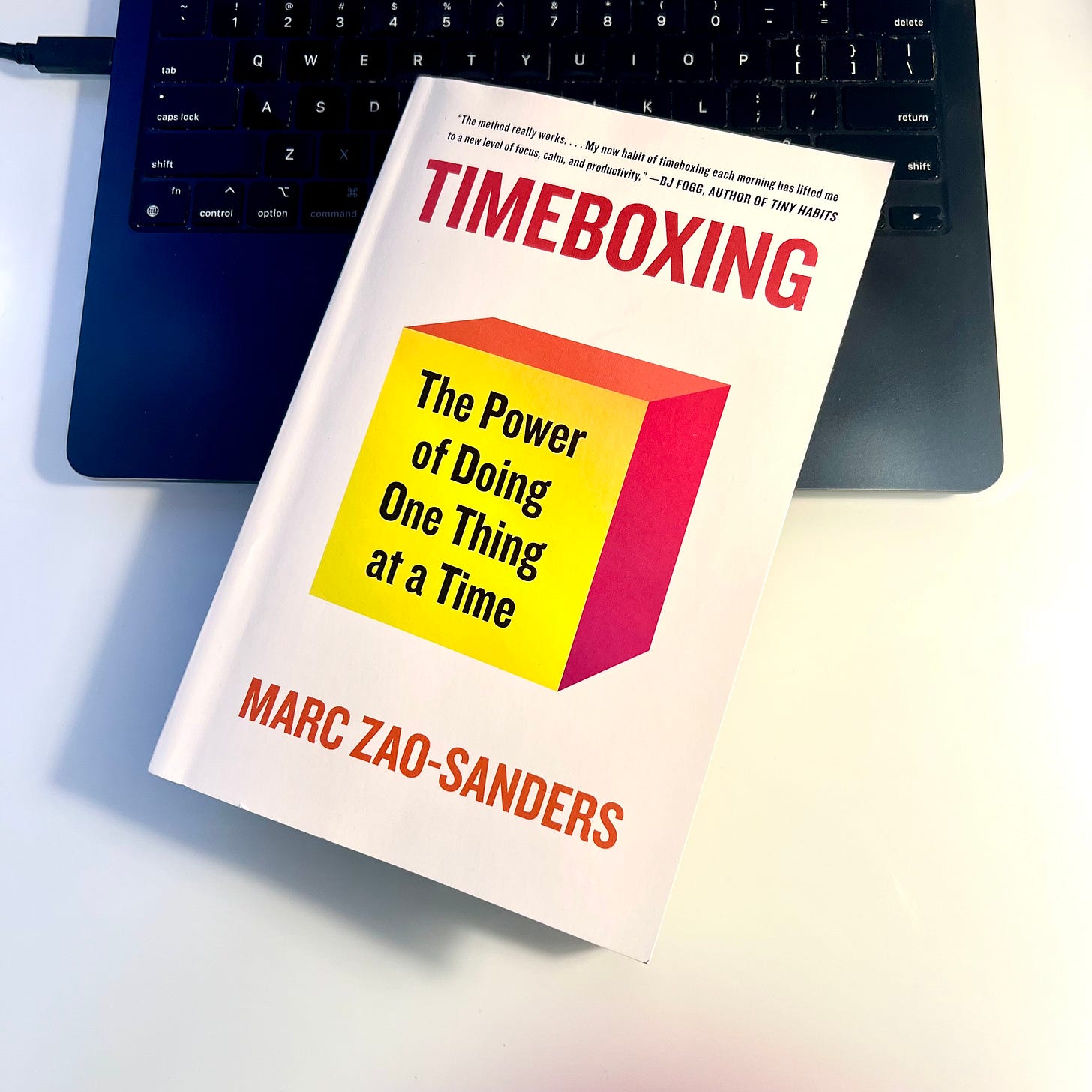

My return to time-boxing coincided conveniently with the recent publication of a book about it: Timeboxing: The Power of Doing One Thing at a Time by Marc Zao-Sanders.3

As regular readers know, Great Work has me reading a lot of prescriptive (‘how-to’) non-fiction on life and work. Getting to the point often involves hours wading through cherry-picked stories about successful US businesspeople and sportspeople, when the book’s point could sometimes be better expressed in twenty well-written pages. Timeboxing exemplifies how to write a useful book about a good idea. It’s intelligent, well-structured, concise, and elegantly written. Zao-Sanders has thought deeply about the whys and hows of time-boxing and about what derails real people from spending our time the way we want to. And it contains more wisdom than I was expecting.

It takes a day-by-day approach: there’s also a week-by-week time-boxing approach (familiar to many from Steven Covey’s enduring The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (1989)—Covey advocated for a weekly focus, and I think it can achieve a better balance of priorities and tasks). And Zao-Sanders’ Timeboxing may be best served alongside Oliver Burkeman’s idea (in Four Thousand Weeks, and elsewhere) about the liberating necessity of accepting the impossibility of getting everything done.

But if you’re interested in how time-boxing could help you and would like a guide to implementing it, this is the book. It’s one I’m adding to the Great Work recommended reading list.

Videos!

As regular readers know, to get my own Great Work book published, I need to grow this newsletter substantially. The message people keep on telling me is “put short videos on social media.” So, with the help of a talented Gen Z friend, I’m cautiously (because I don’t want to get sucked in and I don’t want anyone else to get sucked in) dipping my toe into that water, with clips about Great Work ideas. If you’re on any of these platforms, do consider following me:

Join the community of people who do tough work that matters:

If you found this useful, do send it to others who might too. Thank you!

Oliver Burkeman, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Allen Lane, 2021, page 72.

Email me for citations.

Marc Zao-Sanders. Timeboxing: The Power of Doing One Thing at a Time. St Martin’s Essentials, 2024.

Just a few days ago in the staff coffee room we had a discussion about multi-tasking vs task switching. A small sample size but there was a very strong female bias towards multi-tasking/ task switching and male bias towards task shifting/ time boxing. A lot of the authors of books about the latter approach also identify as male. Got me wondering whether (apologies for sweeping generalisations and simplistic and binary approach here) women are more capable of multi-tasking/ task switching due to neuro-anatomical/ -hormonal differences or whether social/personal expectations mean women feel more pressure to multitask and whether there is a tendency to under perform at work and feel more stressed as a result. On the days I work from home I feel as though I am living 2 concurrent lives - the housekeeper (who is considering how many loads of washing I can get dry on the line, answer questions about where items of lost PE kit are, unpack shopping deliveries, make appointments for children etc) and the worker. It doesn’t feel easy to chunk these separate tasks into manageable blocks. I feel a superwoman at midday juggling everything and buzzing on the cortisol high but frazzled by dinner time as I haven’t finished all the tasks I set myself both at home and at work. (Please note my husband is amazing and pulls his weight equally but we play to our strengths and my strengths definitely are not DIY and being linesperson at son’s football matches etc both activities which are more easily given a designated block of time to complete). Running is great as I can’t do anything else although just realised how many runs I multitask using them as an opportunity to socialise or do jobs (eg collect a parcel) and keep fit! And a final question, please can you explain why my husband has to stop the action of drying up when he answers a question? Is this an example of his complete inability to multitask or is it that he is giving his complete focus to each activity and micro time boxing 😂